Decodable Books and Encodable Writing

The implementation of Systematic Synthetic Phonics in our schools has given us a clear structure and order for teaching grapheme phoneme correspondence (GPC). Whilst there may be some slight variation in the order these sounds are taught, we can see how knowledge can be built and then built upon to go from the simplest words to fluency. One of the most common early GPC sequences is s a t p i n, a grasp of blending sounds in words and these six GPCs enable children to start reading well organised and structured books, in which every word is decodable. As the child grows their knowledge of the alphabetic code, the books they read follow this pattern of development.

The National Curriculum says that pupils should be taught to:

‘Read aloud accurately books that are consistent with their developing phonic knowledge and that do not require them to use other strategies to work out words.’

At this early stage, when the authors of these books are limited to words like pat, sat, nip and pin, the books are unlikely to include engaging narratives. Children will be motivated to read these texts through the success that they are able to achieve.

This often-limited vocabulary and lack of narrative highlights the need for us to read to children and share a wide range of different books (the skill of reading is much more than just decoding the words we see). The use of matched books enables children to get off to a great start with the decoding skill of reading. This strong start is important, and we know reading follows the Mathew Effect: good readers improve faster than poor readers, meaning the gap continues to widen.

PIRLS 2021: National Report for England Research report May 2023 Ariel Lindorff, Jamie Stiff & Heather Kayton: University of Oxford identified that:

‘There is a positive correlation between performance in the year 1 phonics screening check and performance in PIRLS 2021. Several pupil characteristics significantly predict PIRLS 2021 performance in England based on a multiple linear regression analysis. The strongest predictor of PIRLS performance was the year 1 phonics check mark, for which a 1-point increase was associated with nearly a 4-point gain in PIRLS 2021 overall reading performance.’

Having seen the impact that targeted practice and regular application of knowledge can have in reading, are we applying the same principles to writing? How often do we see this type of writing in Reception?

I wt t the sinma in ati jn

(I went to the cinema with aunty Jane)

We ask children to practice reading with words that they can decode, why don’t we ask them to practice writing with words they can encode?

This was highlighted in Ofsted’s Research and analysis –Telling the story: the English Education Subject Report Published 5 March 2024:

‘Most schools do not give pupils enough teaching and practice to gain high degrees of fluency in spelling and handwriting. Teachers rarely use dictation as a tool to help pupils practise spelling and handwriting. In many schools, pupils are expected to carry out extended writing tasks before they have the required knowledge and skills.

In most schools visited, pupils at the earliest stages of learning to write are often asked to complete complex tasks, such as writing a character description, before they have the phonics knowledge to spell the words or the manual skills to form the letters easily and speedily.’

|

So, what can we do to ensure we give children a strong grounding in the basics of writing? |

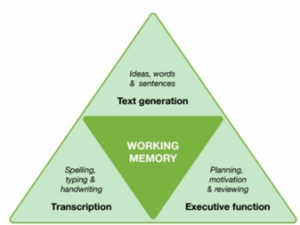

The diagram below is produced by the EEF and is based on the ‘Simple View of Writing’ developed by Beringer et al (2002)

Teach transcription skills with rigour:

- – Additional handwriting practice is needed outside of phonics lessons, this needs to be done with small enough groups for the adult to be able to monitor the process as well as the product. If the letter m looks correct but was written right to left, then this will hinder future fluency. Developing automaticity of letter formation at the early stages of word and sentence writing, enables more of our working memory to focus on the other tasks, such as remembering what word comes next or to leave a space between words.

- – Carefully consider what you are asking the children to write, moving from individual words to simple dictated sentences. If they can’t write it because it contains sounds they don’t know, then don’t ask them to. Don’t try to link your writing practice to a text if it doesn’t work, for example the children cannot write a sentence that includes the words rainbow fish if they haven’t learnt the ai, ow and sh

- – Text generation can be developed separately.

- – Value talking and storytelling. Children need to be able to confidently say what they want to write before they write it. They might not be able to write ‘Jack scurried down the beanstalk as fast as he could,’ but we should plan lots of opportunities for children to develop their story telling and knowledge of sentence structures. By moving to writing too quickly we reduce risking limiting both the writing and the language we use.

- – Read lots of stories to children and read them multiple times.

| Let’s focus on mastering the basics in the Early Years so that we form strong foundations that can be built on as children move through primary and into secondary school. These early stages can be supported through carefully structured decodable books and encodable writing opportunities. |